I hang out with writers and artists along with technical people, and the conversation frequently turns to generative AI, both the text and image kind. The sentiment is rarely positive, and I am sympathetic. I think generative AI is overhyped, the wrong choice for many situations, and is already costing people their livelihoods.

I am a pedant, though, so while I am sympathetic, I get frustrated when I hear that negative sentiment carried by specious and ineffective arguments.

My favorite reason to be cautious is the one I gave last week — What Good is Bullshit? — but today I thought I’d take on some other ways people have of saying “generative AI is a problem”, and fine-tune those arguments to align with the truth as best I understand it.

Tired of this relentless negativity? In Part III, I’ll change my tune and talk about some of the LLM use cases I’m most excited about (mostly ignoring the generative aspect entirely).

“LLMs Cost Too Much Energy”

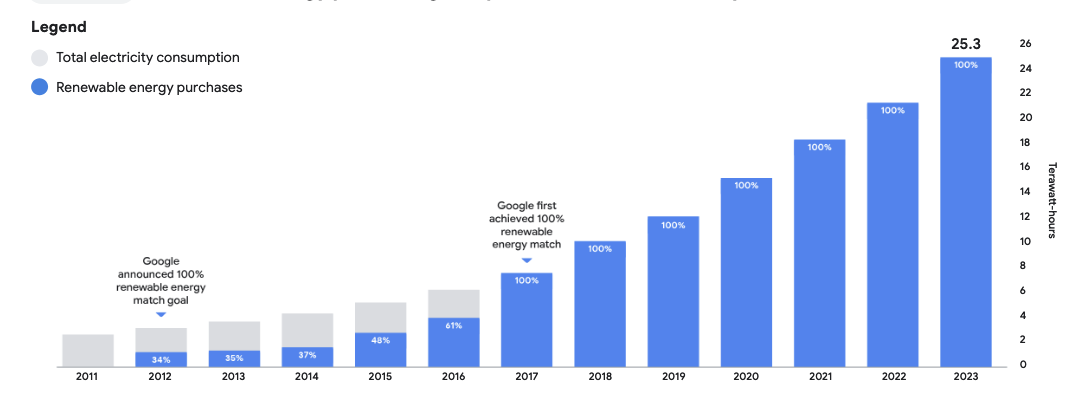

This is, I think, mostly a hold-over argument from fighting against crypto. LLMs do cost energy: training, especially, is expensive, and individual queries are certainly more costly than an average web query; but scary articles about the immense increase in energy usage by major players don’t seem to hold up to scrutiny. While specific energy figures for the major LLMs are largely unavailable, here’s Google’s total energy consumption over the last decade; can you spot the moment Gemini started having its dramatic and damaging effect? (Remember that ChatGPT was released in 2022)

I can’t either.

Too, crypto was doing things that we could already do another way, much faster and much cheaper, with a central database; LLMs are doing something computers couldn’t do before. It’s perfectly fair to argue we don’t need that thing, but it’s a weaker argument, and hard to make the data speak loudly enough for this to be an effective deterrent, I think.

“Training generative models on scraped data is theft.”

Note from Feb 12, 2024: If Judge Bibas’ judgement holds, this section is inaccurate — a direct commercial impact outweighs the fact that the trained work doesn’t appear in the delivered result.

This has a good argument at its core, but it’s almost always phrased in a way that I think is morally complicated and potentially legally unsuccessful.

I’ll pursue the legal argument in the US because that’s the law I’m most familiar with, but I believe a similar framework would apply to any attempt at allowing or banning AI training on open web data in the EU, too. Copyright law is complex, the existing precedent can seem contradictory and confusing, and I’m not a lawyer let alone an international intellectual property lawyer, so take all of this with a grain of salt.

In both cases, the only way an action can legally be theft is if it is by distributing a reproduction. The act of scraping published work and storing it in a private database is not, as I understand it, an infringement. If an article is openly published, you’re allowed to save that article and read it later — in fact just by reading it a copy was made, stored on your computer, and displayed. You’re allowed to print it out, to cut it up, to lick it, whatever. What you’re not allowed to do is sell access to your copy, or make a billion copies to give away: distribution is an infringement.

The question of theft, then, is not in the training process at all; I am not a lawyer, but I’m pretty sure doing even very complicated statistics on open-web data is allowed. The question is whether the trained LLM “contains” the original copyrighted work, in whole or in part; and whether whatever gets distributed (the entire model or merely its output) will contain that data.

The answer is “yes, probably, maybe.” It’s reasonably easy to prove that at least some training data is ‘memorized’ by the model – not just analyzed and abstracted but memorized verbatim. The major players, like OpenAI, are doing their best to add layers on top of the LLM to prevent simple exposure of copyrighted training data – it’s easy to run into a “against terms of service” warning if you try obvious ways of prompting for such things – but the data is there, and can be exposed in more creative ways that don’t involve direct prompting at all: see this paper from late last year.

Because these methods produce random memorized data, rather than specific info, it might be hard to find someone with standing to sue; but in the US, a lawsuit about this would mean a fair use factor analysis, and the ‘market impact’ factor is as large as I think it’s possible to imagine a derivative work having.

I understand that this is a disappointing version of the argument — what creators want is to prevent the training at all, not to allow distribution of a version of the LLM with very careful shackles — but if you made me place a bet on a legal argument working in court, it would be this one. If you can provide court-approved proof that the work is present in the model verbatim, the simplest way for an LLM-builder to prove that it cannot appear in the output is to allow opting out as input.

So I’d rephrase the argument this way: Generative models memorize and reproduce copyrighted material, which is illegal; and they do so in unexpected ways, so the user might not even know the response contains plagiarized material.

“Generative AI can’t be creative, it can only regurgitate old ideas” or “It’s just autocomplete”

This is just straightforwardly a bad take. It’s trivial to get LLMs to generate new ideas. Creativity is easy to extract from randomness; it’s more technically impressive that generative AI can be uncreative, and produce trope-ridden schlock.

Try prompting an LLM with “invent and briefly describe a new art movement” or “describe an unusual artwork made by an imaginary artist”. The results are not necessarily thrilling artistic achievements, and I have no fear of LLMs taking over the conceptual art scene unaided, but they’re not descriptions of anything that exists.

Or, more prosaically, “write a sentence that has never been uttered before”.

You can make an argument about the quality, value, and validity of the ideas an LLM generates, but even shuffling a deck of index cards can generate new ideas from old ones.

“Using it is lazy” or “it takes no skill”

This is an old take. Many clever tools are most often used in lazy ways; but it is more morally sound to criticize the laziness, not the tool. A camera is a lazy way of making a picture — except when it’s not.

The LLM doesn’t determine how much or how little effort goes into the work around the act of generation; the user does.

I hate listening to people talk about using LLMs to write entire stories. But I have no objections to someone using an LLM to find 5 more ways of expressing a sentence when their first two tries didn’t work. Mechanically producing infinite variations on a single theme is something artists have been doing for ages, with whatever technology was available to do so. If the other objections can be dealt with, there’s no reason creative people can’t spend just as much sweat and blood with this in their toolbox as without it.

“Generative AI will cost us jobs”

This is a good one! I think the only tweaking it needs is to be more immediate and particular: “Generative AI is costing jobs.” The scaremongering of “art is dead, creative writers will have no jobs, and it’ll come for you next!” is maybe less honest than “copywriters are already losing work; so are stock photographers and some kinds of illustrators.” An argument about the future implications is hard, and it’s easy to be wrong. An argument about what is already occurring is undeniable, with no risk of being proven wrong in a year.

fin

Are there other arguments against LLM use that you think are more effective? Is your team currently building an LLM into your product, and you think it’s the right choice despite these arguments? Feel free to reach out and bend my ear.