TL;DR

The clothing industry rarely creates dramatically new patterns. It is more lucrative to make small, easy-to-manufacture changes that always use the same basic pattern.

There is therefore lots of room to innovate clothing that is more appropriate for contemporary problems, because basic clothing patterns haven’t changed in decades.

I made some trousers with unusual pockets, and I think they’re good.

Pockets are either ugly or useless

Pockets in tight jeans look bad. Putting a modern slab phone, a wallet, and keys into a pair of skinny jeans will leave even the most fashionable looking like they’re wearing batman’s utility belt as underwear. Even empty, in tight pants a large pocket bag can show through.

The alternative, as many women know from first-hand experience, is a pocket too small to put anything in.

A wallet in the back pocket can cause back pain and bad posture.

Many of us spend most of our time sitting, but all four traditional pockets are totally inaccessible in that position. So we take out our phone, just in case, before we sit down at the restaurant — guaranteeing a distraction.

Aesthetics, storage, and access: these are user needs that are currently poorly fulfilled — and that means things are ripe for innovation.

A brief history

If the space is so ripe, why has there been no pocket innovation recently?

Women used to have pockets. That “used to” has to count back 150 or even 200 years, and those pockets were often a separate garment, either worn underneath and accessed through a slit in the dress, or worn around the hips overtop, rather than built into the dress directly — but regardless, “it has pockets!” as a joyous surprise is a modern invention. (Men’s pockets were also separate pouches if you go back far enough; but going back the same 150-200 years, they lived in the waistcoat and the mandatory jacket; if breeches had pockets they were behind the falls and so, I suspect, not used as much in public.)

The 1880’s brought the 1940s brought the slow arrival of mass production to clothing — not of the textiles, which started much earlier, but of actual clothes. Before this era, clothes were made either at home, or they were made one at a time. (In a quiet resonance with today, this was done in part by women who worked almost entirely from home, only travelling to the workplace to pick up new work and drop off what had been completed).

In retrospect, fashions changed mostly decade by decade rather than year by year, but they changed dramatically. The fashionable silhouette of the 1860s looks nothing like the 1880s, or the 1910’s — so different, in fact, that for women the foundation garments were completely unrelated entities: the crinoline of the 1860s is nothing like the bustle of the 1880s. A person who can cut and sew can sew an incredibly wide range of different things; why not play around?

But with the advent of mass production in clothes factories, the whole layout of the factory floor was based on specific pattern piecing. Each station makes only a few operations on each garment, and garments flow from one station to the next. To completely change the construction of a garment means a radical overhaul of the whole assembly line.

But to simply change the garment’s proportions is easy.

And so we live in a world where every spring the morning talk shows invite someone on to say “this year, [culottes, boot-cuts, skinny jeans, flares, cuffs, boyfriend jeans, high waists, low-rise, acid-wash, raw denim] are coming back into fashion, so keep your eye out!” — but the trousers are made from the same basic pieces, constructed in the same ways, with only the measurements changing. They get longer or shorter, looser or tighter, and change color, but they’re not fundamentally different.

It’s like a lack-luster procedural generation system. Sure, there are technically millions of possibilities, but somehow you still end up bored after seeing the first 5 or 6.

Probably not coincidentally, the advent of mass production is also when women’s silhouettes turned slim, and when all those foundation garments mostly disappeared. Designs that banish structure from the garment and rely entirely on the body beneath are much easier and cheaper to manufacture.

And when silhouettes turned slim, women lost pockets. The more body-hugging the clothing, the less room for pockets — or, rather, the more the pocket contents will show unflatteringly. (And as we know, it would be anathema for a women to show unflattering lump for something as silly as practicality, function, or utility.)

And even as womenswear adopted men’s workwear styles, women got jeans but not the pockets to go with them. Spandex made it even easier to make mass-produced clothes “fit”, and fit tighter. The unsightly-lump factor wasn’t going away.

Even more recently, menswear has returned to an incredibly slim silhouette. Guys in skinny jeans should, by this logic, not have pockets either. But they do.

Women get no practicality and men get no grace.

What if we redesigned the pocket from scratch?

Let’s design a trouser pocket! This process is going to land somewhere between UX and industrial design. I am, sadly, not in charge of a clothes factory, so I am not concerned with the problems of mass-production, but material properties and the construction process do still matter; but I am maybe more willing to make manufacturing sacrifices for usefulness than most industrial designers are able to be.

What do people use pockets for?

- Storing things; most often phone, then keys, wallet or money-clip, and other small items. At the moment, a mask.

- Verifying stored objects — the hip-slapping dance of making sure you have everything before walking out the door.

- They must be secure while standing, sitting, running for the bus, etc

- Things, especially phone, need to go in and out of storage frequently, almost unconsciously.

- Access to phone while seated in a restaurant; to keys and license while in car

- Aesthetically, we want a clean, graceful line from hip to ankle even while holding things.

An initial solution can be based on just three questions:

- Where can your hands reach?

- Where is there extra space to put things?

- Where is there enough support to prevent items swinging around uncomfortably?

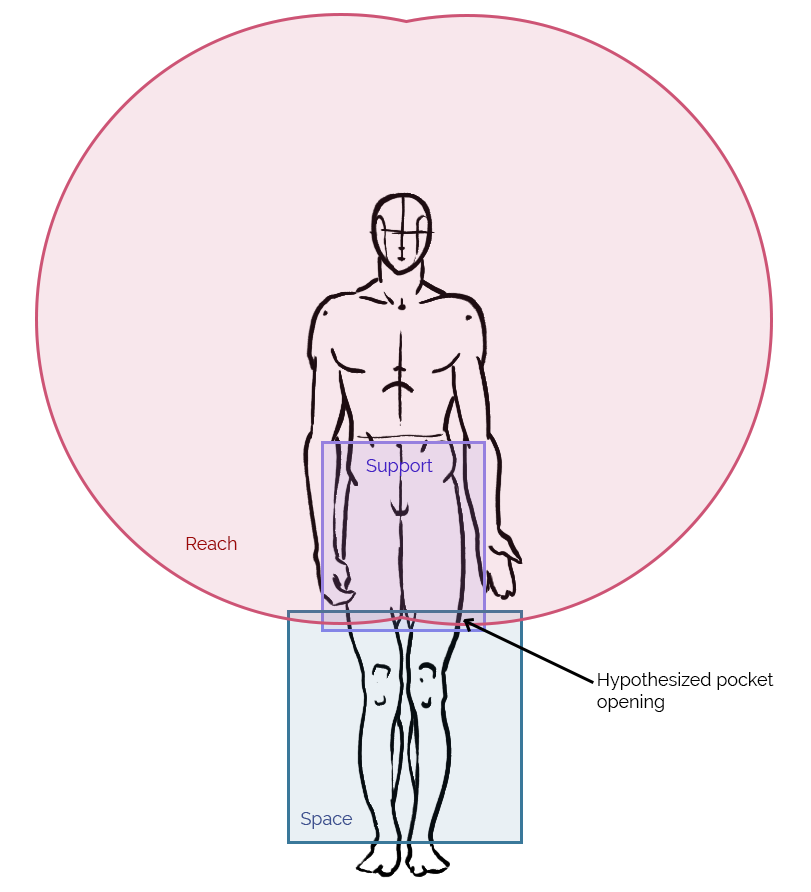

These questions form a physical venn diagram, pointing at a pretty small area for investigation:

You can see that current pockets are located completely outside the area where there is potentially space; the hips and butt of modern pants, for both women and men, are closely fitted. If there’s any ease, it starts just above the knees.

Conveniently, the point where the vastus lateralis starts to curve back in towards the knee, creating space, is also right around the lowest point your arms can reach without bending over, giving us a well-defined target.

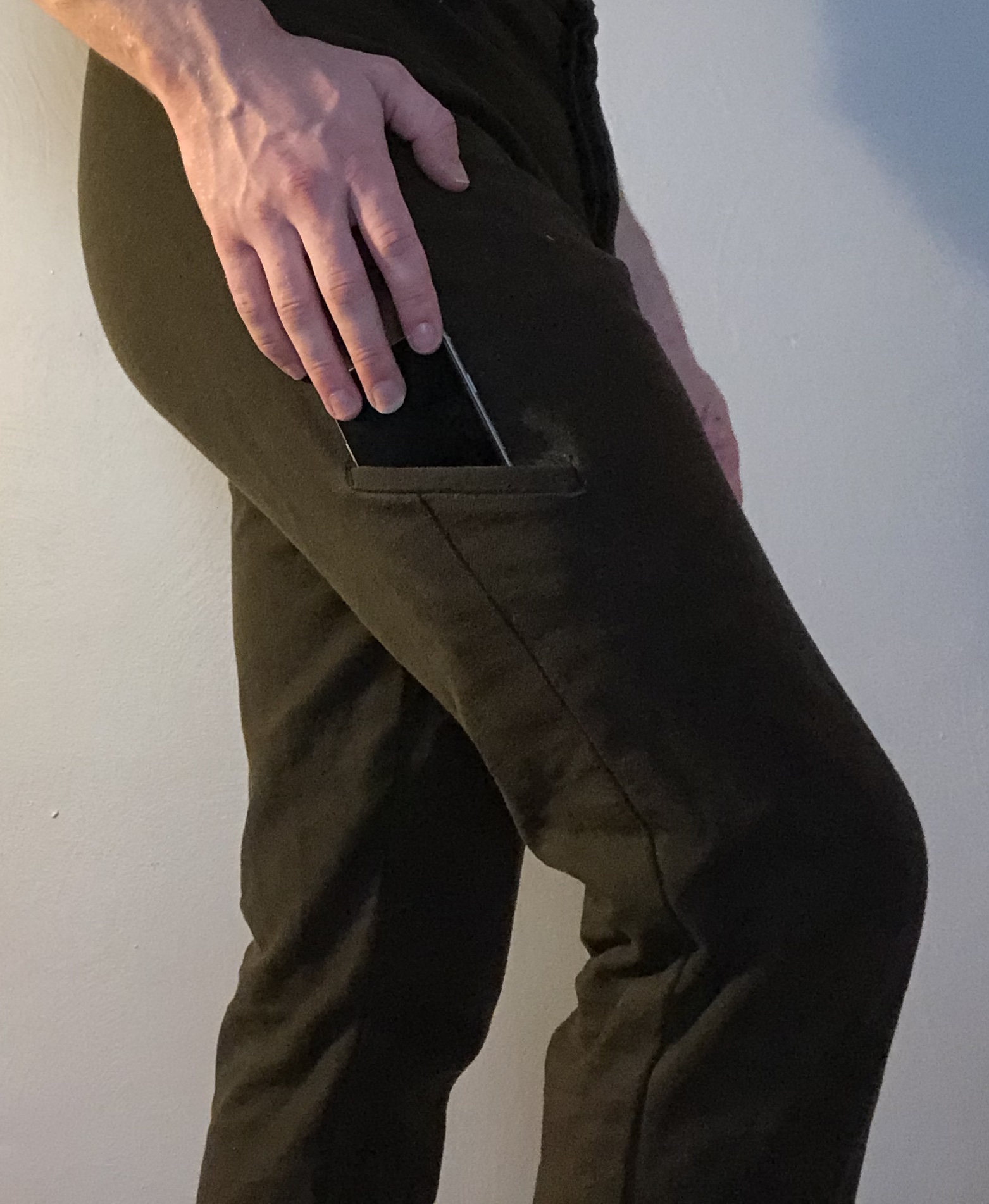

So I made a pair of trousers with no pockets at the waist, and a pair of welt pockets at the side seams, right at that point.

Notes from user testing:

- A pocket needs to be big enough for a whole hand, not just phone, to allow for fishing out small items from the very bottom of the pocket-bag.

- The pocket bag slips down and back if it’s full and the wearer sits down. This is uncomfortable and

- The pocket mustn’t allow a slick round phone to fall out when sitting, especially when, e.g. jiggling a leg.

Revisions

Luckily, each of these notes point at simple revision, rather than the need to start again.

- Make the pockets wider.

- Anchor the bottom of the pocket bag to the side seam.

- Angle the opening so it’s higher in the back — this both makes it easier to slip a phone into the pocket, and makes the pocket “deeper” on the bottom side when sitting or crouching.

Outcome

These are great. I completely forget my phone and wallet are there — they don’t restrict my movement, they’re completely invisible, and yet they’re easy to access while standing or sitting. There’s no temptation to slouch around with my hands stuffed in my pockets. They’re so straightforwardly better for my needs that I’m now frustrated when my new-pocket pants are dirty and I have to wear trousers with pockets that are just SO twentieth-century. I immediately made a pair of jeans in this pattern, too.

Further revision is possible, of course; but while it will be easy to refine this design to suit my personal body and needs more precisely, there’s only so much refinement possible while remaining suitable for a wide range of body types. If you wanted to mass-produce a pocket like this, you’d want to use something like Dreyfuss’ Humanscale data to make sure the placement and size is appropriate for the widest range of people. Luckily, you’d have some additional information in the sizing of the rest of the pants.

Appendix: Sam, have you simply invented cargo pants?

No. Cargo pants solve different problems for different people.

If cargo pants are appropriate for your daily life, you definitely don’t want or need my side-seam welt pockets; and vice-versa. Cargo pants aren’t office-wear; these dress pants aren’t combat-wear.