(If you’re not interested in the how or why of this project, and just want the result, it’s available here.)

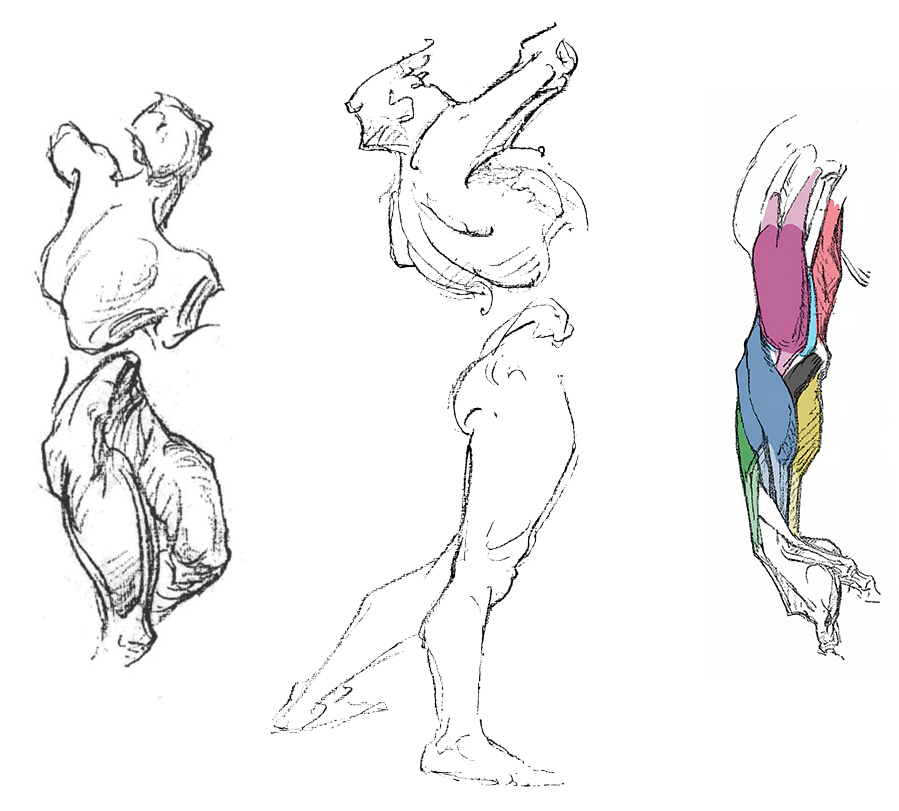

Bridgman’s Constructive Anatomy is a classic study text for artists that has been in print for over a century. It’s time-tested and artist-proven: comic book artists, illustrators, and fine artists all study Bridgman. Other anatomy books may be more complete, more technical, more clear, or more accurate — but Bridgman’s drawings look like art. Any attempt to improve or correct Bridgman would be foolish! An act of hubris!

Last year, I set out to improve and correct Bridgman.

In my defense, this project didn’t start with that goal. I only wanted to do a more in-depth study of Bridgman for myself. Bridgman writes in a way that’s both dated and pretty convoluted. So, to prove to myself that I was truly digging in and understanding it, I decided to rewrite the text, paragraph by paragraph, into modern words. English-to-English translation: how hard could it be?

(Unavoidably, complications are sure to follow. This is a story of scope creep, as much as it is about writing or drawing.)

Almost as soon as I began, I discovered that some of the texts challenges were more subtle than the individual sentences being difficult to parse.

The Cryptic

Take, for example, the case of wedging. Bridgman has this to say, on the very first page of his text:

Masses of about the same size or proportion are conceived not as masses, but as one mass; those of different proportions, in respect to their movement, are conceived as wedging into each other, or as morticed or interlocking.

The effective conception is that of wedging.

Throughout the rest of the work, he will point out when forms should be thought of as wedging. Bridgman does not, however, ever define the word; he never illustrates the difference between two masses wedging into each other and any other form of contact.

I studied every time Bridgman used the word, both in this text and in others. I turned to other artists’ attempts at decoding the word. In the end, I came up with an analysis that I believe is effective, and that’s plausibly what Bridgman meant by the word, but there’s simply not enough evidence for my multi-page description, with new illustrations, to feel like a translation.

I hadn’t even gotten through Bridgman’s half-page introduction and already I was forced to think about how to distinguish between his ideas (if rephrased in modern words) and my own additions and analysis. This was the first hint that I would not end this project with a plain text file of notes.

Layout, Laid Out

Some problems with Constructive Anatomy are due to the constraints of affordable bookmaking in the 1920’s: none of the illustrations are in line with the text, and of course, they’re all in black and white. But other issues are deeper and more structural. Bridgman is miserly with his explanations: he rarely explicitly illustrates an idea if he’s described it, and doesn’t always describe an idea if he’s illustrated it. When the text does directly refer to an illustration, they are almost never found on the same page.

I couldn’t just rewrite the text and get anywhere. I had to connect the illustrations to the text, and (where necessary) make their labels easier to follow. I spent a week slicing out each of the 500+ illustrations and re-sorting them based on what they were attempting to show. This was another judgment call; the original text alternates pages of text with pages of dozens of uncaptioned drawings. It’s very likely many of those drawings were intended to demonstrate more than one idea. Moving them in line with the text makes it easier to connect them to one idea, but also easier to ignore any other lessons they might be trying to teach.

Due to the order he visits the body parts, Bridgman is forced to repeat himself to avoid using anatomical names he hasn’t yet defined. Once I was bought in enough to move all the illustrations, reordering the sections seemed obvious and necessary.

It was probably around this point that I started to consider the fact that George Bridgman died over 70 years ago, and his work is in the public domain, now: I could, legally, publish the result of all this work.

A Product of His Time

Other challenges are due to the social era: Bridgman’s anatomical vocabulary is sometimes outdated, and a few times completely incorrect (to be honest, I remain uncertain where he thought the brachioradialis or levator scapulae belonged; eventually I gave up trying to understand and put them in the correct places). His terminology is old-fashioned, and his anatomical analysis is, at least on one notable occasion, overtly racist.

Some important bits are completely missing. He ignores the female figure entirely – there are feminine faces and hands, but no feminine bodies appear anywhere in the entire book. In a course on anatomy for fine artists, he never mentions the breast. Some of his other books at least include a few female nudes, and I was able to pull in some of them to fill in gaps; but any discussion of how to make a body more stereotypically feminine or masculine in appearance, I had to write from scratch.

Wait, Is this product design? Again?

As I worked, I began asking other artists about their experiences with Bridgman. I started approaching the project less like a student and more like a product designer. When someone mentioned that their eyes glazed over at the Latin names, I started adding silly mnemonics to help make them easier to hang on to. I adjusted my color palette to be colorblind-friendly and began thinking about how the colors functioned across multiple illustrations, rather than just within one. I thought long and hard about how far I could go while remaining true to the meaning and spirit of Bridgman’s original curriculum.

Bridgman fills an important role, not because he’s the most technically accurate or comprehensive resource — quite the opposite! — but because he makes explicit aesthetic choices about how he wants to draw the human body. Studying his work is only partially about gaining the knowledge of a med student, and much more about discovering and showing your own sense of beauty in the same set of parts. His text has many insights about how to think about (and draw) the human body, and I’ve tried to preserve and expose those insights. But there are lots of texts out there that will name the muscles and bones and visible landmarks. Bridgman is special because his drawings are beautiful, rather than just illustrative.

The more I honed in on the experience I wanted people to have when studying Bridgman, the easier it was to make difficult decisions about what to keep and what could be left in the past.

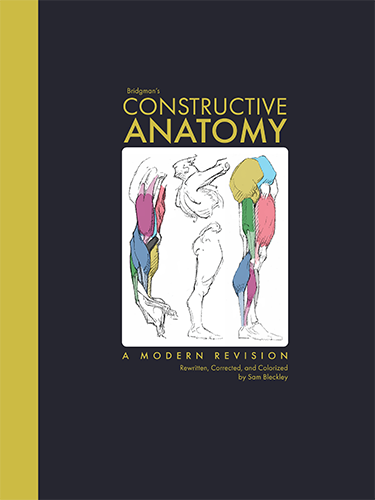

It’s a book!

I’m proud to say that the result of all this work is now available for purchase, in a luxurious studio reference edition, with full color where necessary and big, note-taking-friendly margins. You can pick up a copy here:

Bridgman’s Constructive Anatomy:

A Modern Revision on Amazon

It’s (not) a Living

“Wow, Sam.” I hear you say. “Is rewriting and improving public-domain texts a way to earn a living? A passive income?”

No. This project is turning out to be more successful than I expected; I’ve sold one or two copies a day since I launched it. There was no need for the complicated pre-launch strategies a normal book needs because people are already searching for (and buying) “Bridgman’s Constructive Anatomy.” Because the text is in the public domain, it’s not hard to siphon off some of that traffic. There are a handful of people doing so (less successfully) without having even bothered with improving the text.

But it’s a beer money project. If no one bought the original Constructive Anatomy and they all bought mine instead — complete market saturation — I would still net less than $5000 a year. And even if I wanted to repeat the trick with a different book, to double up that payday, there just aren’t that many books in a similar position: public domain, relatively well-known, and deeply flawed in ways I have the skills to recognize and correct.

That’s not a disappointment — I’ve known that this wasn’t a money-maker from the start — but I’ve seen a few people get an entreprenurial glint in their eye as I’ve talked about this project. Keep your feet on the ground.

Appendix: Runes

Almost every illustration from the original book made it into my revision. A number of illustrations from Bridgman’s other texts also made it in and I created a few dozen new illustrations to fill in gaps. A handful of originals, however, didn’t make the cut. Here are a few Bridgman doodles that, even after many months of extensive study, I remain unable to interpret, at least in terms of what lesson they might convey to a student of art or anatomy.